In 1984, the two nightclub impresarios who had run Studio 54 opened a new chapter in the lodging industry with Morgans, a boutique hotel known for its sparse décor, lack of outdoor signage and popularity among the young and the cool.

Natalie Keyssar for The Wall Street Journal

The NoMad's library

Today, there are dozens of boutique hotels in New York, with new ones are opening all the time. But their designs, décor and overall vibe are quite different from those developed by Ian Schrager, the late Steve Rubell and other pioneers.

![[image]](http://si.wsj.net/public/resources/images/NY-CI237_NYSPAC_DV_20130505211637.jpg)

Natalie Keyssar for The Wall Street Journal

The NoMad Hotel at 1170 Broadway;

Thread counts have remained high but, in openings of the past year or so, décor has grown more opulent and interior spaces that would have once housed sleek bars are far likelier to contain plush restaurants. An age of hotel descriptions that featured terms like "inextricably hip" has given way to a much franker invocation of luxury and history.

John Taggart for The Wall Street Journal

The lobby at the Jade

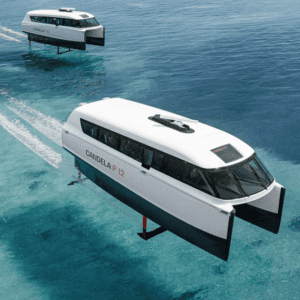

"When Ian Schrager pioneered the lifestyle hotel the model was hotel as nightclub; today it's about all day," says Andrew Zobler, owner of the NoMad hotel, a 168-room hotel that opened in Spring 2012 near the Flatiron District.

![[image]](http://si.wsj.net/public/resources/images/NY-CI235_NYSPAC_DV_20130505211400.jpg)

John Taggart for The Wall Street Journal

The Jade Hotel at 52 W. 13th St

This change partly reflects a coming of age of the scenester-with-reservations. Those initial generations of boutique hotel guests that partied until dawn have shifted their priorities to a good night's rest.

"As the clientele of the lifestyle hotel industry matures, it's about being fun but also more important about providing comfort and luxury," says Mr. Zobler.

Designers say the historical look of the new boutiques is warmer than the modernist form. "The problem with this minimalistic moment is that people like it only for a short time. People want places where they are at home," says Andres Escobar, the Montreal-based designer of the "Prohibition-styled" Jade Hotel that opened in February in Greenwich Village.

The lodging industry was an anodyne place when Morgans opened. Other than the most high-end of offerings, operators seemed to pride themselves on being as far from hip as one could get.

The boutique hotel model changed this, typically offering luxury accommodations in locations more intimate than chain hotels, while carrying a nightclub feel. This model proved a galloping success, spreading around the world to about any city with some claim to cosmopolitanism. Customers were able to feel special, cared-for and cooler than those frumpy tourists and business drones at the hotel chains.

"Hotels are a kind of mythical social space that is very specific," notes David Rockwell, designer of the W hotels in New York.

Many of Mr. Schrager's initial project interiors were designed by Phillipe Starck, whose whimsical minimalism defined a generation of projects. They offered a sleek look dappled with theatrically eccentric touches in contrast to sterile chain and over-gilded luxury offerings.

Night life frequently played a large role, and still does. Places like the Standard, the Maritime and the Jane are often better known for what happens outside of their rooms during evening hours. New York magazine has referred to the "nightlife-hotel complex"-just check any "society" photo slide show lately to confirm the notion. These hotels often harbor large lounge or bar spaces and make explicit efforts to book high-profile events.

But a number of newcomers are taking a different approach. The gilded NoMad, drawing design inspiration from its 1905 Beaux-Arts structure and designer Jacques Garcia's former Paris apartment, boasts a Parisian-style restaurant flowing into the lobby of the hotel and furniture modeled after French originals. The Jade Hotel has similarly ornate décor, in Mr. Escobar's account, an evolution from earlier trends.

"Comfort comes by virtue of a collection of objects-everybody, whether designers, lawyers or engineers, collects items because something makes them feel at home," he says.

Home at the Jade involves Art Deco lamps and rotary phones, which certainly isn't "home" for most, but it's a much closer feeling than the average hotel. The exterior was redesigned with the aim of neighborhood architectural harmony, featuring cobbled brick and limestone touches.

Meanwhile, the Refinery Hotel, located in a former hat factory in the Garment District, has suffused its design with nods both to the millinery and the building's Neo-Gothic exterior. Room table legs are modeled on vintage Singer sewing tables; the entrance way is both vaulted and lined for part of its length with rondules; "gothic," whether "neo-" or otherwise, isn't a descriptor common in earlier iterations of the boutique model.

To be sure, not every hotel has followed suit. For example, the Wythe Hotel, which opened last summer in a former barrel factory in Williamsburg, offers a rawer industrial aesthetic and a burgeoning social calendar.

But judging from these most recent openings, luxury and history may be supplanting hip as a promotional buzzword. The Quin in Midtown, has foregrounded luxury and art in its promotion, with a comparatively subdued midcentury aesthetic, drawing structural inspiration from both nearby Carnegie Hall and the Steinway piano showroom.

Even some early-wave boutique hotels have embraced new looks as part of recent renovations. The original Morgans was renovated in 2008, acquiring such very contemporary trappings as an overhead LED display, but also a lighter color palate a few shades removed from nightclub-dusky.

"The hospitality industry has transitioned toward spaces that feel more residential and comfortable," says Verena Haller, Senior Vice President of Design at Morgans Group.

Source: The Wall Street Journal