Late last year I spent a few days in Medellin (Colombia). For many people, the name Medellin will be associated with the ultra-violent rule of the cocaine cartel chief Pablo Escobar. In fact over the last 20 years Medellin has undergone a remarkable and heartwarming transformation. But that link to Escobar remains through the emergence in tours to key sites associated with him – dark tourism.

Dark tourism

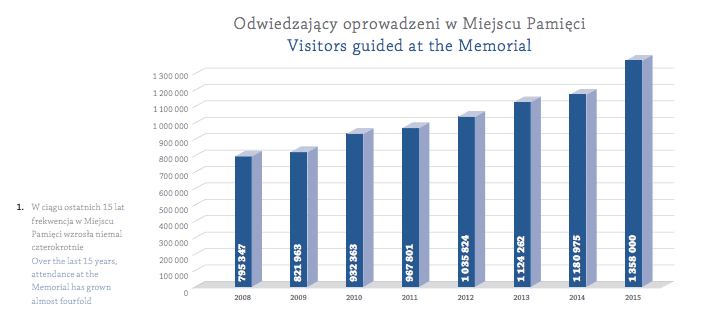

The tour is one a growing body of experiences known as ‘dark tourism’: defined as any travel associated with death, suffering, murder, pain, disaster or the macabre. Other examples range from sites associated with the Jack the Ripper in London to visits to the Killing Fields in Cambodia. The increase in tours and the establishment of an Institute for Dark Tourism that seeks to identify what is happening in this field and what is best practice reflects a growing demand. To take just one example, visitors to Auschwitz grew 40% in 2015 (see chart below). But the need for such an institute also acknowledged the complexity of the subject and the challenges it represents.

Many such sites are places of trauma and memory for both survivors and locals. Returning to the example of Medellin, when the tours launched the city was seeking to change and did not want to be reminded of such recent traumatic events.

There are also concerns about trivialising the events (for example, the tourists who take selfies at Auschwitz) or glamorizing the perpetrators at the expense of the victims which was the fear for the people and placemakers of Medellin when they saw the emergence of Escobar tours.

How to manage dark tourism

So should you allow dark tourism and, if you do, how do you manage it to overcome these concerns?

Firstly and most importantly the community (and where appropriate victims or survivors) must be consulted from the beginning and throughout the project. There needs to be acknowledgement of their needs and stories. Where controversy cannot be avoided, communication needs to be sensitively managed. Where possible my advice is always to ‘own the story, not the point of view’ – acknowledge valid multiple interpretations (i.e. not those of deniers) and help people find their own way into the story of the place.

Where infrastructure is required, the design of the site should be reflective of these needs and sensitive to the place or the circumstances. Brief thoroughly to get the best design you can afford. Careful decisions need to be made about what and where to preserve or renovate versus leaving things in their natural condition – again based on consultation.

The quality of interpretation is vital – so invest in ways to bring the story alive and to personalise it. The design of the infrastructure should support the interpretation (not the other way round). A fantastic example of this is the Apartheid Museum in Johannesburg. Visitors entering the museum are randomly assigned to be Blanke (White) or Non-Blanke (Non-White) – they enter the museum through different entrances and the first part of the journey goes through different corridors but all the while visible to one another. When I visited with friends, I was the only one randomly assigned to the non-white corridor – it was a very physical measure of the impact of apartheid to be separate but in sight of others and made the later exhibits more meaningful.

Make it about people – tell individual stories

At Port Arthur in Tasmania when you take a tour of the historic penal colony you are assigned a persona of an historical person and see the site through their eyes. Port Arthur is also an interesting example of this consultation and design because there are many layers to its history. In 1996, it became the site of Australia’s worst ever mass shooting (and was instrumental in the historic changes to Australia’s gun laws). Interpretation and information on this more recent event is handled very differently from the older stories. It is more low key and respects the fact that for many Tasmanians – including some who still work at the site – that this is a very personal issue.

Don’t assume saying nothing is better

The site of the Fuhrerbunker in Berlin (where Hitler lived his final days and died) was initially concealed and no memento placed there. This was due to a very natural desire to avoid creating a focus for Neo Nazis. But the absence of acknowledgement or interpretation lead to a growth in rumours and myths – many of which were ill-informed. So at the suggestion of Berliner Unterwelten (Berlin Underworlds) an interpretive panel now marks the site. As Holger Happel of Berliner Unterworld says this was done “to put a stop to the invented stories.” In this case, acknowledgement actually demystified the site.

Port Arthur came to a similar conclusion about its modern dark associations. Whilst some wanted no memorial, others needed a place to grieve. In the end, that need won out.

Just because you can, doesn’t mean you should

I often counsel clients that “just because you can, doesn’t mean you should”. There are many who feel uncomfortable with dark tourism. In his commentary on the “Auschwitz selfie” Lilit Marcus noted that we should celebrate the lives of the victims and that trivialization was inevitable if we bring mass tourism to sites of suffering and evil. Whilst I understand his point of view, my own is very different.

Firstly, I think it casts travel solely as being about entertainment. For many people that is true. But for others travel is essentially about learning and personal growth. The evidence is that this sort of travel is growing. Visiting sites such as Auschwitz are occasions for profound reflection and learning. This is particularly true if you combine them with visiting Kazimierz and Podgorze (the former Jewish area and ghetto site in Krakow). The power of the contrast is so important in understanding what was lost. This is also visible if you visit the Schindler factory- now an outstanding museum to the Nazi occupation of Krakow.

Secondly, I feel it is more authentic to include those darker experiences. If you are visiting Krakow and only see the positives of this beautiful city, you aren’t seeing the whole story.

Perhaps some trivialisation by ‘tick list’ traveller visits to such sites is inevitable. But I also see an alternative perspective on this. When I visited Auschwitz in 2014 it was very crowded. Do I think some of those visitors were ‘tick list’ travellers? Of course. But perhaps the impact of the site was even greater for those travellers than for those of us who came with some knowledge.

Whilst my partner is someone who seeks engagement when travelling, he is less interested in this period of history and these issues than I am. He is also someone who places a high value on order and structure. So seeing his experience of looking at how the administrative thoroughness of the Nazi machine made possible what happened as Auschwitz was powerfully moving. I am sure that many people who went casually were even more affected than he was. Reaching people who don’t seriously reflect on these issues is such a valuable opportunity in terms of social outcomes from tourism.

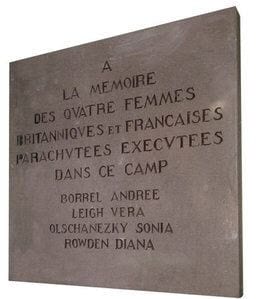

At the museum on the site of the former Natzweiler-Struthof concentration camp there is a monument to four women Special Operations Executive (sabotage) members who were executed there in 1944. The final monument is very simple (see image) but when the design of the monument was being considered it was suggested that the words of the poet Walt Whitman were used (Source: A Life in Secrets, Sara Helm, 2005, Abacus): ‘Only the dark, dark night shows to our eyes the stars”.

If we operationalise and market it correctly that is exactly what dark tourism can do.

About the author