CEO magazine reported in 2016 that in a survey of over 100,000 people they found that the most valued leadership quality is by far honesty (89%)

CEO magazine reported in 2016 that in a survey of over 100,000 people they found that the most valued leadership quality is by far honesty (89%)

Our survey of hoteliers was somewhat more modest with over 760 respondents, but when asking the question “when interviewing for a leadership position which of the following characteristics are you looking for in a candidate?”, the response was the same with honesty being ranked the highest.

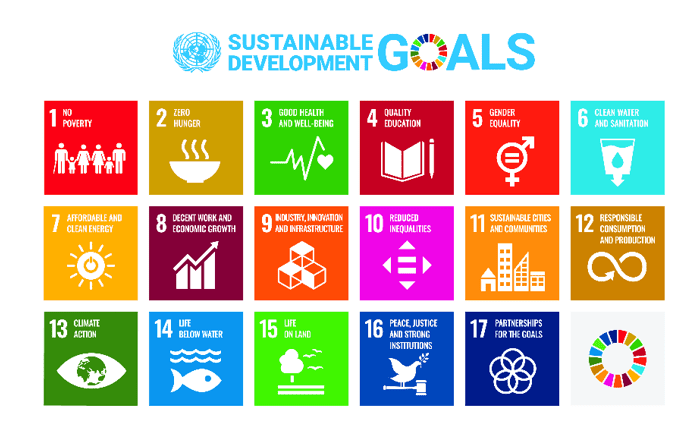

Yet whilst honesty may be the quality valued in individuals, is it equally found in the businesses or organisations that they represent, or does the corporate culture override personal beliefs and behaviour? There is evidence that the millennial and the younger generations of employees are now looking for different values in their employers and their businesses. They have a greater sense of moral purpose and are looking for transparency in the way the business operates. They are aware that there is often a mismatch between the values they expect of the leader, of honesty and integrity, that are not reflected in their day-to-day behaviour in running the business.

These conflicts have been cited in some studies as the result of either performance appraisal systems or the primary focus on short-term profit and loss. The pressures to perform to these criteria are often at the expense of the longer term social, cultural and environmental values that are becoming more and more important to the younger generations. The Dalai llama is quoted as saying “A lack of transparency results in distrust and a deep sense of insecurity” and this in part is contributing to the increasingly common view that businesses often behave in an ethically irresponsible manner with a lack of honesty and transparency.

It is easy to excuse lack of transparency by quoting commercial sensitivities but this does little to improve the increasingly sceptical unease in the public image of a business and its executives. It is equally true that the public have even less belief in the honesty and transparency of political leadership, but where hospitality businesses are competing with each other for guests and customers, those customers, especially the younger generations are looking for much more evidence and demonstration of corporate social responsibility and honesty and transparency in those dealings.

This trend is equally true of employees and with continuing staff recruitment demands against a diminishing supply, employees have a much wider choice of potential employers. There is increasing evidence that the pay and reward system on its own is no longer sufficient incentive for potential employees but they are looking at the actual behaviour of businesses as a demonstration of their wider social responsibilities. There is a clear generational change in attitude that is happening now.

For the hospitality executives they can be in situations where they’re choosing between the commercial necessities of the profit and loss account and the conflict with their conscience. A study for Düsseldorf Institute for Applied Marketing Science, revealed an interesting distinction. Middle management often feel under more pressure and experience greater moral conflicts than those at the senior level of the organisation. Whether this is because the senior executives are further removed from the implications of such ethical choice or that they have become more immune and immersed in the corporate culture and behaviour, must be a matter of debate.

Hospitality businesses have to cope with numerous customer and staff situations where pressure on management will often lead to institutional resistance to transparency with the first reaction to either deny or cover up. Both courses of action are dishonest and as soon as this level of dishonesty is recognised by both customers and employees, longer term damage results. There is a greater truth in the saying “honesty is the best policy”.